My favourite pair of black trousers came from Jigsaw almost five years ago. I can date them because I was on my way to the cinema to see the Frances McDormand film Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri, which I remember because I left the bag containing them under my seat in the cinema and had to jump off the bus and run back – and Google tells me that the film was released in January 2018. I think they cost around £60.

I paid less than that for the ivory silk shirt I’m wearing with them today, which I bought from Marks & Spencer in 2016 from a collection curated by Alexa Chung. My leather belt is from Gap and may well be older than either of my children, one of whom is at university.

There is nothing unusual about this outfit, except that we have come to think of high-street clothes as landfill-in-waiting. It is estimated that the average garment is worn only 10 times before disposal, according to the Pulse of the Fashion Industry report for 2018 by the Global Fashion Agenda and Boston Consulting Group. Research by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation suggested that the average number of wears before disposal was lowest in the US, then China, followed by Europe and then the rest of the world. Exact figures are, for obvious reasons, hard to pin down, but what is clear is that the number of times a piece is worn has decreased by an estimated 36% over the past 15 years.

Such shocking statistics rightly highlight an urgent problem, but they don’t tell the whole story. Telling the stories only of clothes that get tossed in the bin risks giving the impression that high-street fashion is inevitably disposable. If we shrug and accept the notion that only expensive designer clothes are made to last, we normalise treating high street fashion – the only option on the vast majority of budgets – as a throwaway option.

But there is another story, one that is illustrated by a rummage through my wardrobe, where designer clothes and high street ones rub shoulders. The beaded chiffon Dior dress I bought from the Bicester Village outlet for my 40th birthday party hangs between a 2014 Kate Moss for Topshop number with off-the-shoulder ostrich feather trim and the & Other Stories LBD with a deep band of faux fur at the hemline that people at fashion parties assume is Prada.

My shoe cupboard has Choos and Manolos, but for the Fashion Awards last week I reached, as I very often do, for classic black patent courts from Russell & Bromley, which I’ve had for ever and are reliably comfortable.

This is not just me. Lucinda Chambers, founder of the online shopping site Collagerie, has an archive of designer names accrued over 25 years as a fashion editor of Vogue – but also “a Mango handbag that I look after as if it’s my firstborn child”.

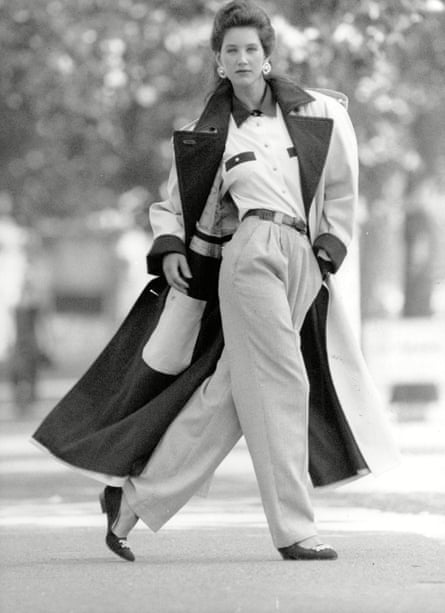

A quick poll of friends and colleagues reveals prized high-street treasures: a double-breasted crimson wool coat from H&M, almost a decade old but good as new; a Jil Sander for Uniqlo blazer that is as well-fitting, and now as irreplaceable, as couture. A timeless cropped tuxedo jacket bought from the now-defunct Dorothy Perkins. My sister often wears a pink-and-black graffiti-print Tammy Girl dress that our mum bought in the 1980s.

Finding high-street pieces that last means knowing how to shop. Price wars in the fast fashion space have lowered standards of production, and many clothes are neither as well thought-through nor as well-constructed as they were during St Michael-era Marks & Spencer, or in the golden age of Topshop under Jane Shepherdson, or the first designer collaborations at H&M, when limited editions were produced at a minimal cost margin as a loss leader.

But there are still bargains to be found. Shop in store, not online, because feeling it by hand is the only true way to assess fabric. Look at the weight and quality of fastenings: flimsy zips or chipped buttons are a red flag of corners cut. A snagged or unfinished seam will sag into a misshapen silhouette after a few wears.

Think through how the piece will age: I never buy clothes with a stripe or print that includes white, because white can’t stay white if washed with other colours. Shopping in a bricks-and-mortar store rather than clicking to buy on screen is also a useful filter for editing out impulse buys. If queueing for the changing room feels like too much effort, that’s a strong sign you don’t love whatever it is enough to justify either the cost or the carbon footprint.

And once discovered, treasures need to be treated as such, whatever their provenance. Delicate silks and satins must be washed cool and air dried; party shoes taken to a good cobbler for replacement heel tips.

Investment dressing isn’t just for the rich. The crown jewels of your wardrobe aren’t the clothes you spent the most on: they are the pieces you treasure. The price on the tag hanging from your new jacket is meaningless from the moment you snip it off and wear it for the first time. In other words, don’t be a snob. The true value of the clothes in your wardrobes is up to you to decide.